How We Work is an interview and essay series by Contrary dedicated to surfacing insights about important parts of the economy that have gone unnoticed or under-explored by the startup ecosystem. It profiles the people who power the modern world and the tools, systems, and processes they interact with every day.

***

Every time a light switches on in the US, a sophisticated system for generating and transmitting electricity is at work behind the scenes. This system has slowly built up since the emergence of the first commercial power station, Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Station, in 1882. Its continued function relies on the diligent but rarely-noticed efforts of a legion of engineers and operations professionals working to keep the lights on in America.

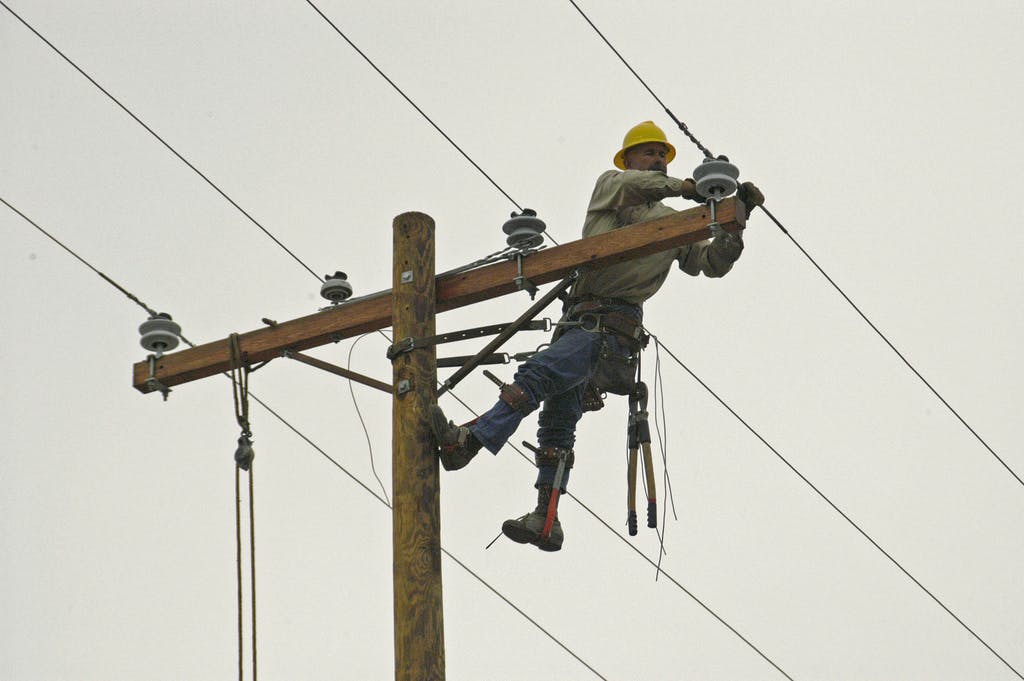

One of the more visible – and yet rarely celebrated – roles within that system is that of the lineworker. Lineworkers are tasked with a deceptively simple job: keeping every home and business in the country powered and connected at all times. That involves building out new wire, repairing broken poles, and performing routine maintenance – often while suspended forty feet above the ground.

The job of the lineworker predates the existence of the power grid itself. In the 19th century, the first lineworkers were tasked with putting up wires to carry telegraph messages. Though early telegraph lines were strung across trees and other high points of the natural and human landscape, it quickly became apparent that purpose-built poles would be far better suited for establishing a network of elevated wire across long distances and uneven terrain.

These early linemen, as they came to be known, built the first parts of what would become America’s sprawling telecommunications infrastructure. Their duties were physically demanding and often highly dangerous. Safety procedures and protective equipment were practically nonexistent, and electrical systems in general were poorly understood. Though the Bureau of Labor Statistics did not begin tracking work-related injuries and fatalities until later in the 20th century, it was reported that anywhere from one-third to one-half of early lineworkers were killed on the job.

The advent of the electrical power grid in the 1880s marked a significant expansion of the lineworker’s role. Building upon the existing telegraph network, they were charged with constructing an expanding system of poles and wires to bring power to homes and businesses across the country. Lineworkers were obliged to develop a working understanding of transformers, circuit breakers, and other electrical equipment. The job also became significantly more dangerous due to the high-voltage power systems lineworkers now had to contend with.

In the 21st century, the US is grappling with the challenge of modernizing an aging electric grid. Thanks to smart grid technology, increased power demand from electric vehicles, and the ongoing renewable energy revolution, America’s electrical grid, which is in reality a complex patchwork of interconnected regional grids that are owned and operated by a multitude of entities, requires significant upgrades and strengthening. A significant portion of this upgrade work is and will continue to be undertaken by lineworkers working for local utilities and municipalities.

Despite the onward march of technology, the core tasks of a lineworker – like climbing poles, handling wires, and ensuring the ongoing flow of electricity – remain central to the job. To understand that job, we spoke to Bryce Conner, a lineworker who has worked for the City of Seattle for seven years on both maintenance and upgrade work.

Key Takeaways

Source: NARA

1. Other than fixing damage, smart grid upgrades and strengthening the grid are the biggest parts of a lineworker’s job in 2023.

The ‘smart grid’ is a term for the bundle of technologies currently being implemented on the electrical grid through ongoing upgrades. Smart grids use automation and advanced communications and control technologies to increase efficiency, reliability, and sustainability. The fundamental purpose of a smart grid is to create an electric power system that is able to react dynamically to changes in supply and demand, as well as to automatically detect and respond to system problems. It’s a key part of building a grid prepared for the challenges and demands of the future of energy consumption, which will need to incorporate both greater renewable sources of supply while also accommodating increasing demand.

Lineworkers help implement smart grid upgrades by installing new equipment including switches, lines, and transformers. They also benefit from the upgrades, which make it easier to diagnose and respond to problems when they arise, as well as energize and re-energize specific parts of the system without causing service interruptions.

Bryce describes what he perceives as the biggest technological improvement of the grid over the past two years: switches that self-isolate, meaning that parts of the network can be effectively depowered automatically and remotely, “as opposed to having somebody driving around throwing switches and waiting for a truck to get out there to isolate.”

2. Loss of knowledge is a major concern for lineworkers as a whole generation looks toward retirement.

Loss of institutional knowledge is a major concern for many technical industries and trades. When experienced professionals retire or move on, they take with them years of expertise and unique insights, creating a knowledge gap that can be tough to fill. Nuances and subtleties of a particular role or field can often be learned only through experience, which isn’t easily transferred in the absence of very robust systems.

The risk is particularly acute for lineworkers because they operate in a relatively small, specialized field where much of the expertise is learned on the job and can be highly specific to the particular systems a lineman works with. It is also a physically demanding career, often leading to early retirement.

As early as 2005, the US Department of Labor was describing the approaching retirement cliff for lineworkers as a “critical concern”. The department further reported this year that upwards of half of the utilities workforce, in general, was up for retirement by 2030.

As a lineworker, Bryce has witnessed this knowledge attrition firsthand. As a specific example, he described how many of the lineworkers with working knowledge of how to troubleshoot and maintain underground power lines are heading for retirement, and that he is doing his best to learn from them on their “way out the door”.

3. There has been a major generational shift towards safer practices.

Lineworking is dangerous. The 2005 Department of Energy report described lineworking as “one of the highest paid professions in the United States that does not require a post-secondary education”, which it attributed to the job’s hazard level.

The quality of equipment and training has improved drastically over the past few decades. Lineworkers today are equipped with safety gear such as insulating gloves, hard hats, safety glasses, flame-resistant clothing, and fall protection equipment. The materials and designs used in these items have improved over time, and a lineworker in 2023 will be working with equipment that is lighter, more comfortable, and more effective than those of earlier generations.

One such piece of equipment is the “hot stick”, an insulated fiberglass pole used to manipulate wires, so a lineworker can do their work from a safe distance. Regulations on their use vary from state to state and even between utility companies, with Bryce saying that his home state of Washington is a “hot stick state” where they are mandated.

Bryce also reports that lineworkers now have a much better understanding of electrical system safety, and that “old timers” maintain processes that are less safe and find it difficult to adapt to the new mindset around risk reduction.

Full Interview

Introduce yourself and tell us how you got into this job.

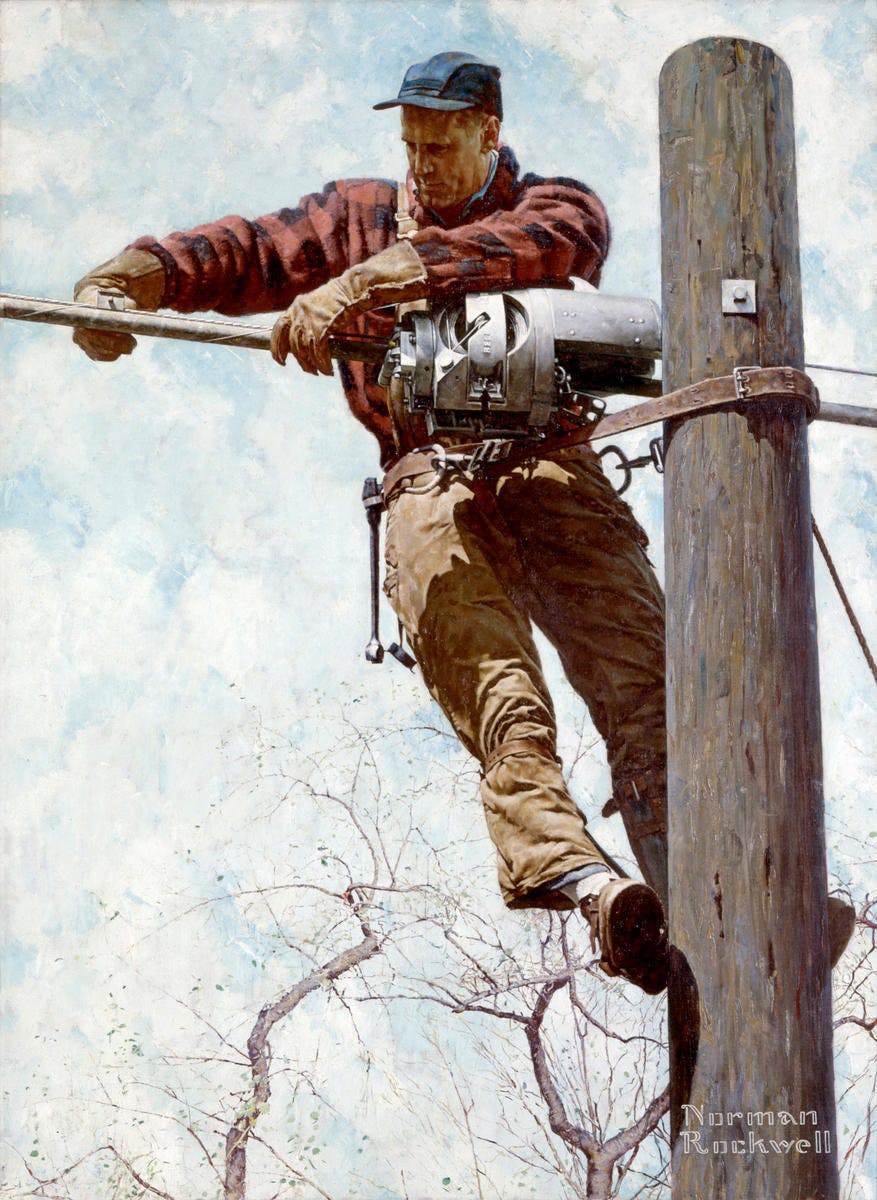

I'm a high voltage lineman, journey level lineworker. It's the job description. Journeyman lineman would be the non-gender-neutral way of saying it. I work for the city of Seattle, and I’ve been there for a little more than seven years. I got into it because there's a Norman Rockwell painting I liked called ‘Lineman’. So it wasn't good career guidance or anything like that.

But I always wanted a union gig. I was doing non-union carpentry, just building houses, and went and tried out for it. It took me a little while to get into the apprenticeship. It’s a four-year apprenticeship, and then you become a journeyman. You learn the trade, and then you get a journeyman ticket. And theoretically, you could go anywhere with that, but I’ve only ever worked at one utility.

Source: Norman Rockwell Museum

Is that apprenticeship working under one lineman, or is there a variety of different people who are teaching you?

It's a pretty good variety. So there are rotations, and you're on a new crew every month. Basically, there are two sides of town in Seattle and six or seven different overhead crews on each side of town, and then another five or six underground crews. So you rotate through pretty much all of those.

There’s also a systems operations center – kind of like the air traffic controller equivalent – that you rotate through for a couple of weeks and then a couple of other little departments that you rotate through, including smaller crews called ‘line service’ that are just single or two-person crews as opposed to bigger overhead crews of four or five.

Walk me through an average day for you.

So, I pretty much show up at the yard and hope there is some scheduled work. But a lot of the time you have to prioritize outages.

Scheduled work will usually be full changeouts, transformer upgrades, adding new services, or dropping out services. We do a lot of putting in 480-volt transformer banks, which is just a bigger power bank. Transformers for cranes and stuff like that. Seattle's got a lot of construction going on. We do flagging and protection of our high-voltage line for new high-rise buildings that are going up. Basically just making sure that our power lines are where they’re supposed to be and trying to keep people out of them.

There’s longer-term work, like getting put on a reconductor job [which is] where you're moving out all the existing wires and pulling in new wire. You try and keep [the power on] all the time because obviously, people don’t like losing power. So that’s system upgrade stuff, and there’s a fair bit of that. But more often than not on the day-to-day, it’s changing out rotten poles and responding when people hit poles with their cars.

Would you say your job is more routine upgrades or responding to emergencies?

That's a good question. When I started it definitely felt like more scheduled work. We are down a bunch of linemen, and we lost a bunch of guys because we had a vaccine mandate and I work with a lot of country guys who really didn't want to get the shot. So we lost a fair amount of people.

So the more people we lose, the more it feels like my job is responding to emergencies more than it is scheduled work. I wish I could say it was a higher percentage of grid-strengthening work, but yeah.

When it comes to that grid strengthening or upgrade work – is that just something that comes with the growth of the city, or is there new technology being rolled out?

I think it's just kind of ongoing. I don't entirely understand how the city assigns it. There's an ongoing change to better technology for how switches talk to one another. That's just so that we can re-energize faster, and keep people out of power for less time.

That's sort of the main technological upgrade of the last 20 years: switches that self-isolate and minimize outages. As opposed to having somebody driving around throwing switches and waiting for a truck to get out there to isolate. So that's kind of the ongoing upgrade side of it, and we run fiber lines for that.

How much time do you actually spend on the line on your average day? You mentioned being underground as well.

Yeah, a fair bit. I guess it depends on the day. I've definitely been up for, you know, 14 hours straight, on a really bad couple of poles or whatever. But on the average day — just the service upgrades and stuff — it’s an hour at a time, knocking out four or five jobs. And then you go back to the shop and rack out all the salvage. So it's not the whole day. I'd say I’m up in the air, you know, 50-60% of the time.

And what about underground work? How does that differ?

That stuff is pretty different. There are more connections and more things that could go wrong. There are different terminations and it's kind of a different ballgame in general. I’m still kind of humbled by that stuff on occasion.

I was on an outage like that last night. Overhead wires are pretty easy to run out even if it's dark — you're usually gonna be able to find the problem pretty quickly. Underground wires are not really the same. There's a process for testing and it's not like the wires are gonna fall out of the air or go to ground, and it can be pretty tough to find the problem.

Whereas when there’s an outage with an above-ground line, you can usually see that it has fallen down, or something is visibly severed, right?

Yeah. More often than not it’s a clear and present problem with an obvious solution. Like yeah: there’s a pole on the ground, or someone’s driven a Cadillac through it. Pretty apparent troubleshooting.

As I go along I'm taking more of those underground calls. And some of those guys are retiring — guys that are really dialed in on the troubleshooting aspects of underground work and just knew our system really well. Those guys retire and you lose all that knowledge with them. So I’ve tried to catch some of them on the way out the door.

What are the main tools you use when you’re on a job?

There are two main tools. The first would be your hooks and climbing spurs.

You kind of look like a cowboy when you're walking around with them on. They're on the inside of your foot. We spend a lot of time in those during the apprenticeship, and I still climb poles I can't reach with the truck or even just to get the job done faster. I find it's better positioning to be on the pole than bent over on a bucket truck. You can get your work in a little closer to you.

The first six months are really all about learning how to climb, getting in repetitions, and doing it safely. Some guys care about doing it faster — we got rodeos here where people climb and ring a bell or do a hurtman rescue or something. They train and drill you pretty hard on hurtman rescue, so if somebody was ever hung up [on the line] you'd be able to go up and save them.

So that's the big one, the hooks and climbing spurs. The other one is the hot stick. We’re a hot stick state, so instead of using rubber gloves like some places do we use insulated fiberglass sticks which are tested and rated for high voltage. So we don't touch the high-voltage wire directly. We use the sticks, and there’s an art to that.

Source: American Public Power Association

Is there a division of labor or specialization in a lineman crew? Do you have some guys that, say, put up new poles whereas others repair broken lines? Or is it more generalized?

It’s all one team. Let’s say something unexpected happens — say you get a call in the middle of the night that a pole has come down, and you go out there and try and make it safe. At that point, the call’s already gone out to get a pole, and there's a separate crew that drops off the pole. We would maybe wait to re-energize if there was damage to the customer side at the weatherhead, which is where the wire goes into a residence or a business. If there was some issue on their panel, we'd probably hold off on re-energizing.

Then we're the crew that dig the hole, set the pole, transfer the wires — all of it, start to finish. We're definitely all supposed to be capable of doing whatever. “A lineman is a lineman is a lineman” is kind of the joke we tell. You should be able to do everything. But, that said, we have operators on the crew, we have ground people. The ground people are more tasked with digging the hole and running the truck that sets the pole. And then we have a crew chief who holds a clearance and is a safety watch. So that's kind of the main distinction.

So if you have a four-man crew, you'd have two in the air and two on the ground.

You mentioned a control center which is the equivalent of an air traffic control center. Talk a little more about that. How does that work?

So there is one central windowless room called the SOC (System Operations Center). And they are able to monitor pretty much everything on the power transmission and distribution side. Most of our power comes into Seattle from hydroelectric dams up in the mountains, and they’re monitoring on the generation side of things too.

On the distribution side, it’s all high-voltage mapping. So if we were working on something, and we didn't feel like we could safely do it hot, or if there was a cutover and we needed to de-energize, there’s a list of people who are qualified to hold a clearance. That basically means they call in and get permission from SOC to open and isolate a wire.

There’s a specific verbiage they need to use, and you have to repeat it back exactly as they say it to you. And then you have that wire and it’s assigned to you. That means you can work on it and nobody will energize it on you while you work.

Do you have to interface much more than that with the people on the power generation side of things? People in grid operations and engineering who are more involved in the generation and transmission of power?

I don't, to be honest with you. There’s sort of a disconnect there. There are not as many people working in generation as you might think — they’re kind of a skeleton crew. I really haven’t talked to many of those guys. I’ve been out to our hydroelectric projects and worked there a little bit, but mostly on our side of it. I leave it at the dividing line.

They’re sometimes there on the radio, but the contact is pretty limited. I hadn’t actually thought about that as a disconnect, but there you go.

Are there any other big safety processes that come into your job?

Safety is kind of an ongoing thing. There are some old-school ways to deal with things that people still do, and my class was taught differently.

Not that I want to be disrespectful to the old timers, but we’re trying to bring some methods up to standard. You know, you’re never supposed to put your hands on a wire unless it's tested and grounded. ‘Equipotential bonding’ is one that some of the old timers have a tough time wrapping their head around. That’s the classic ‘bird on a wire’ example, making sure that you’re at the same potential as the wire you’re working on. Some of the old timers are pretty happy doing some more frowned-upon methods of grounding. There's still a little bit of that cowboy mentality to the trade.

Have you observed any changes — beyond the labor shortages you mentioned — in the time you’ve been doing it?

Yeah, there's definitely ongoing changes in just the culture of it for sure. More technology comes in and different trucks are coming in. I’d like to think we're safer now than we ever have been, just talking about people taking risks and stuff like that.

It seems like our management is pretty accommodating for us taking longer to do something right and do it safely. I'm not sure that that's always been the case. You hear about the linemen of yesteryear and how much they got done in a day, and you kind of wonder where they were cutting corners.

On the technology side — it’s not like crazy new tech, but just like better insulation on things, different lifting technology. The same type of trucks, just newer models. Different fiberglass tools are coming out, different mounting brackets. Nothing world-changing.

Disclosure: Nothing presented within this article is intended to constitute legal, business, investment or tax advice, and under no circumstances should any information provided herein be used or considered as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy an interest in any investment fund managed by Contrary LLC (“Contrary”) nor does such information constitute an offer to provide investment advisory services. Information provided reflects Contrary’s views as of a time, whereby such views are subject to change at any point and Contrary shall not be obligated to provide notice of any change. Companies mentioned in this article may be a representative sample of portfolio companies in which Contrary has invested in which the author believes such companies fit the objective criteria stated in commentary, which do not reflect all investments made by Contrary. No assumptions should be made that investments listed above were or will be profitable. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events, results or the actual experience may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in these statements. Nothing contained in this article may be relied upon as a guarantee or assurance as to the future success of any particular company. Past performance is not indicative of future results. A list of investments made by Contrary (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for Contrary to disclose publicly, Fund of Fund investments and investments in which total invested capital is no more than $50,000) is available at www.contrary.com/investments.

Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by Contrary. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, Contrary has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Please see www.contrary.com/legal for additional important information.